Thursday night I went into Soho for my weekly rehearsal with the Antelope Dance Project and Prince Street was full of news vans and police trucks and barricades. And for once, it was something real — not a movie, not

Thursday night I went into Soho for my weekly rehearsal with the Antelope Dance Project and Prince Street was full of news vans and police trucks and barricades. And for once, it was something real — not a movie, not the NYPD showing off for the tourists a terrorism-response drill, not a wildly inappropriate response to a political protest. They were digging in the basement of the building on the corner for the body of Etan Patz.

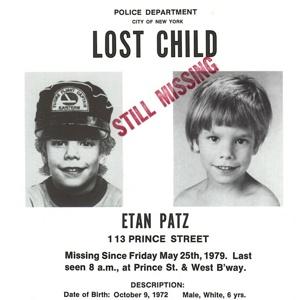

Nobody else at the rehearsal remembered that name, but I don’t think anyone at the rehearsal lived in NYC then. Most of them weren’t even born when he disappeared, back in the spring of 1979. I was about to graduate eighth grade, and I didn’t pay much attention to the news. But that summer, his bucktoothed smile and blond bangs were everywhere. I suspect that quite a few non-white kids who weren’t the children of artists disappeared in NYC in the 1970s, but he was the one who made the news, the first one to have his picture on the milk cartons we looked at over cereal, the one who grabbed the attention of a sheltered 14-year-old kid in Staten Island.

Soho has changed so much since then. That was the year I first started going into Manhattan by myself (and kudos to my parents for allowing it, in that atmosphere). I would go to the Compleat Strategist on 33rd Street, or Baird Searles’s Science Fiction Shop on Eighth Avenue (past all those nice women on 14th Street who always waved hello), or to the pre-superstore wonderland of Barnes and Noble on 5th and 18th, or to the Strand. But I didn’t go to Soho. Why would I? There was nothing there, just long dark streets. Even years later in college, I thought of Soho mainly as the somewhat risky last-ditch place to park when you couldn’t find a space in the Village.

And now? A few weeks ago I got to rehearsal and realized I needed batteries for my recorder. Just outside the studio on Wooster Street, there are plenty of stores selling high-end handbags and shoes, although that night only one was open, and that for some kind of reception for overdressed anorexics. But no real stores, nothing for normal people living normal lives. I had to walk three blocks, past West Broadway (where Etan’s bus stop was), to find a deli where I could get some batteries.

Thursday night I sat in the pre-rehearsal circle with the dancers, and talked about how it felt to run into that story from my childhood again. Had he lived, Etan would have been older than everyone in the room except for me. He might have had children going to school themselves. We concluded the circle and the dancers began their warmups. I usually play for the warmups, not the music I play for the show, but a completely in-the-moment improv. This is what I played Thursday night, thinking about a little blond boy and long dark cobblestone streets, about this piece of history jutting into shopping-mall Soho, surrounded by tourists and shoppers staring back in time at a world they had never seen.